1 Commitment

Focusing on your career

I had completed my freshman year at Johns Hopkins University with a respectable GPA, so I felt comfortable asking my parents if I could spend the summer in Baltimore to take organic chemistry. This would position me to complete my premedical requirements ahead of schedule, take the MCATs at the end of my sophomore year, and apply for early admission to medical school at Hopkins. At this stage of my education and career, saving a couple of years in an already lengthy education and training continuum would be appealing to my parents as would any additional scholarships or loans I could obtain. A few of my friends who had similar ambitions chose to take organic chemistry at a local university close to their homes because it would be “easier and a lot cheaper.” I was also familiar with the running community in Baltimore and thought I could continue my training regimen uninterrupted. I neglected to disclose this to my parents, but I suspect they knew I had other motives for staying in Baltimore that summer.

The first four-week session was intense and did not go very well. Let us just say I underachieved, mostly because I had overestimated my ability to handle the fast-paced curriculum. I had been spending too much time training versus studying in what proved to be a very concentrated and rigorous course. Many similarly motivated premedical students from other highly competitive universities on the East Coast had also decided to take summer organic chemistry at Hopkins to better position themselves for early application to its medical school. On reflection, my friends had probably made the better decision in taking organic chemistry closer to home in a less intense environment with fewer distractions.

During the first week of the second summer session, I had just finished a workout and returned to the house where I had been staying that summer. As I was walking up the steps, I saw my father sitting on the stoop of the house wearing a business suit. He greeted me calmly, saying, “Hi son. I thought I would surprise you and drive up from my meeting in Washington DC to see how you were doing.” My father was never one for surprise visits so I was certain he had something very important he wanted to discuss with me. Our conversation started with catching up on events at home. I was immediately relieved that his visit was not related to something bad that had happened to someone in our family.

He took me to a local Baltimore restaurant that evening. At the end of dinner, my father took a deep breath and said, “Son, since you were a little boy, you have always talked about being a physician.” There was another long pause before he continued, “You need to decide what is important.” My father did not mention my fixation on running. The phrase “you need to decide what is important” will resonate with me forever. I felt I had let him down. My father never needed to repeat this conversation with me. He knew I had lost sight of why I had decided to take organic chemistry that summer and of my goal to become a physician. He shared some personal stories of crossroads in his life and career to communicate that life’s distractions can present challenges and test our commitment to a career path. My father had never been so introspective or willing to share his thoughts with me. I think he felt it was time for me to make a commitment to my education and career.

When I was a first-year internal medicine resident, my father passed away from stage IV lung cancer. I was devastated when my mother called to tell me his diagnosis. As fate would have it, I was on a hematology-oncology rotation. I had just enough information about my father’s diagnosis and tests to pull aside my oncology attending after morning rounds the next day. He was solemn as I described my father’s diagnosis and the test results. When I finished, he told me he was very sorry but it was important for my family to focus on my father’s quality of life for his last few months. I was not expecting such blunt counsel.

One of a medical resident’s responsibilities when covering the oncology service was to provide end of life care to oncology patients, and complete the official paperwork to include recording the time and cause of death. Each time I had to fulfill this responsibility, I struggled with the somber task of completing the necessary paperwork. I often took some time to read the patient’s personal and family history in the chart. I could not comprehend this would be my father’s fate soon.

When I told my mother I was exploring a transfer to the Internal Medicine Program at the University of Arkansas to be closer to them, my father immediately came on the phone. I should have known he was listening to our conversation. He firmly stated, “Son, you chose this program, and you need to stay there to fulfill your commitment!” followed by, “I am going to be OK.” I knew this was the end of the conversation. I didn’t make the transfer. I have no doubt my father was proud of me as he would have felt saddened if I had altered any aspect of my education or career due to his illness.

I took a brief leave of absence from my residency program to attend my father’s funeral in Arkansas. Residents in the program took care of my clinical obligations, call responsibilities, and patients for the time I was away. It is notable that none of my colleagues asked for or accepted my proposal to repay their efforts when I returned, despite my offers to repay their kindness. I am forever grateful to my colleagues for their compassion and generosity.

Several of my father’s colleagues made a point to find me after the funeral. I did not know most of them but they knew me from hearing my father’s stories. I was amazed how much they knew about my life and career aspirations. I had not been aware of the mannerisms I shared with my father that several people pointed out, including our facial expressions and the intonation we used when we spoke. I had always thought we were so different when I was growing up. I was comforted to know I had retained some of my father’s traits. People told me how much my father had meant to them. I especially remember the words “kind”, “supportive”, and “committed.” When I mentor junior colleagues, I often reflect on my father’s support and counsel at formative stages of my life and career.

Key Concepts

- To achieve your career goals, you will need to commit to a long education and training continuum with anticipated sacrifice.

- When distractions cause you to second-guess your career goals, family and close friends can often serve as a vested support system.

- Throughout your education and training, continue to revisit your commitment to a chosen career path to better define your priorities.

Your beliefs, attitudes, and attributes are foundational components of your identity, both now and in the future. The core values that are the foundation of your personal identity are established early in life but continue to evolve throughout your education and career. Your family and socioeconomic background, ethnicity, and religion provide important context and perspective as you deal with early life experiences. These experiences teach you to navigate successes and failures as well as assess your strengths and weaknesses. Professional relationships and activities as well as early academic challenges are useful for assessing your adaptability and resilience. When you encounter both positive and negative role models, you begin to appreciate and internalize the more positive values. Over the course of your training, you have opportunities to observe role models in various areas of practice who share your ideals and interests, and these observations can lead you to identify a future occupation that aligns well with your core values and aptitudes. Early aspirations that you find mirrored in your role models can reaffirm your career path as you begin to envision your future professional identity. These aspirations for a life and career are appropriately idealized, and role models can help you visualize them.

While your clinical work will be important, pursuing an intentional career focused on your professional growth and development can provide opportunities to find added fulfillment in your personal and professional life. In my academic career, I committed more time to supervising students and trainees while delivering clinical care at a teaching hospital, giving lectures, and directing education programs than I did in my prior career focused exclusively on my work providing clinical care in a private practice setting. I have never regretted my decision to pursue pediatric fellowship training and remain in an academic practice given my love of teaching and mentorship, but I would never condemn a colleague who made a different value judgment based on the satisfaction they derive from their clinical practice.

In 2018, the American Association of Medical Colleges (AAMC) estimated that 75% of medical students would graduate with debt, and the median debt at the time of graduation would be $200,000. This amount of debt has only increased over the years. For medical students, the amount of debt already accrued, the rigors of their chosen training program and future career, and the total length of their training continuum often guide their career choice. My advice is to seek counsel from more senior practitioners in a specialty to decide if the sacrifices that may be required are reasonable compared to the satisfaction and fulfillment these colleagues have found in their careers. This type of value judgment is one of the most important components of choosing a career path in medicine.

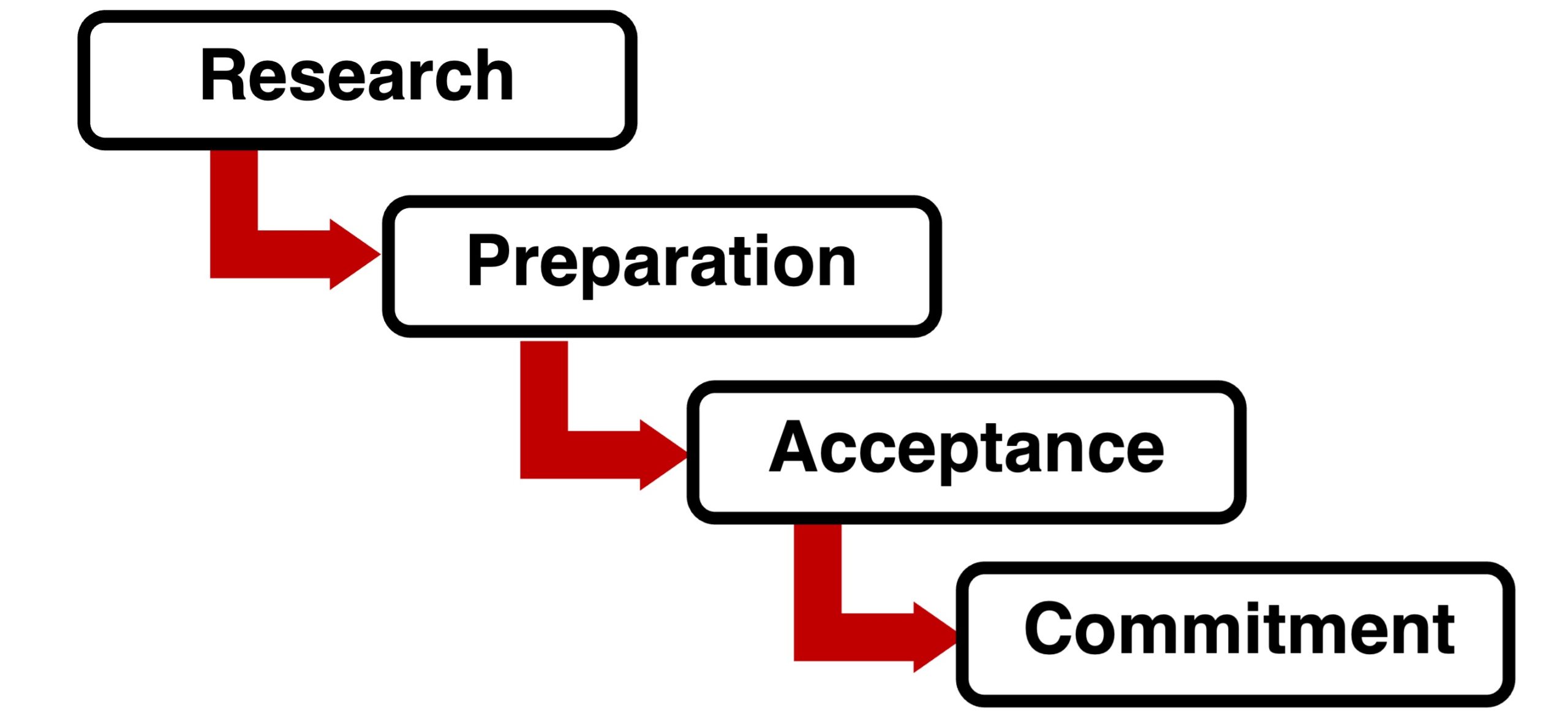

Stages of commitment

Discovering your professional career path requires research regarding the training and certification requirements to practice as a fully credentialed practitioner in a specialty. While the adage “If you love what you do, you will never work a day in your life” is true for many, the bigger challenge is discovering the work you love that provides fulfillment proportional to your commitment and sacrifice. Role models who have found balance and satisfaction in their careers can provide you with added insight and stoke your motivation to persevere. If you have difficulty envisioning your life and career following a similar path as a role model, seek guidance from experienced career advisors that are positioned to provide objective counsel regarding alternative career paths. Advisors and supervising faculty can also provide formative and summative feedback to a student by reviewing their academic record. Identifying areas of strength helps align a student’s aptitudes as well as their interests with a compatible career path. This type of preparation is necessary for you to make a fully informed decision. More medical schools are adopting the practice of having students and trainees participate in self-reflective activities to assess their commitment to a career path in medicine as a component of their professional identity formation.

Your dedication to a long education and training continuum entails your acceptance of many realities, including an understanding of the expectations for acquiring the knowledge and attaining the level of skill necessary to become a highly competent practitioner. For those contemplating a career as a clinical subspecialist, researcher, or educator, your training is extended even further. Delaying a decision to pursue additional training such as a master’s program in business, science, or education until you have completed medical school and postgraduate training provides time to fully assess the value of this added training. Considerations include your stage of life, family commitments, debt, and opportunities to explore the value of this training to advance your career. Academic departments often support a physician’s training if they feel it benefits one of the department’s academic or clinical missions. At some point, you should feel better informed and able to commit to the additional training necessary to achieve your long-term career goals.

A lifelong commitment to your career is possible after you have become a practicing member of a specialty and developed both meaningful peer relationships and a better understanding of the expectations for you as a professional in that career. This socialization process often takes several years, inclusive of your time in a training program. Long training continuums that include residencies and fellowships as well as postdoctoral studies provide you opportunities to observe role models and receive counsel from accomplished mentors. These observations of physicians at various stages of their careers position you to better assess your own long-term commitment to a profession. As you begin to internalize all aspects of your chosen specialty, it is reasonable to revisit and readjust the focus of your career.

Suggested Reading

- Cruess R, Cruess S, Boudreau D, Snell L, Steinert Y. Reframing medical education to support professional identity formation. Acad Med (2014) 89:1446-1451. DOI: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000000427

- Zhang C, Kuncel N, Sackett P. The process of attrition in pre-medical studies: a large-scale analysis across 102 schools. PLOS ONE (2020) 1-15. DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0243546

- Bellini L, Adina K, Englander R. Providing compassionate off-ramps for medical students is a moral imperative. Acad Med (2019) 94:656-658. DOI: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000002568