3 Identity

Discovering your professional identity

Surgery was my first clinical rotation in medical school. This followed two years in the classroom studying anatomy, pharmacology, physiology, biochemistry, and other basic sciences. I had enjoyed many aspects of the basic sciences, especially anatomy: I devoted several hours each week to attending lectures and dissecting a cadaver with my team of three other medical students. We took turns as the lead for each session with members of the team offering opinions about how best to proceed with the dissection. Our group ethos included helping each other prepare for exams, which were particularly stressful given the hundreds of possible structures we could be asked to identify and formally name using the original Latin term. I did not appreciate until later how formative anatomy lab would be as one of my first collaborative learning activities, providing perspective and preparation for a future career as a physician and educator. An equally important aspect to anatomy was acknowledging that our cadaver had been a person who made the very personal decision to donate their body to further the education of future physicians. I remember our team sharing very personal and thoughtful perspectives about this altruistic contribution to our education, wondering if we would be willing to replicate this gesture at the end of our lives.

I was surprisingly self-confident when I arrived at the hospital to prepare for morning rounds. It had been communicated to new third-year medical students coming on-service that we should arrive early in the morning to begin gathering information about our assigned patients. I had already contacted the medical student who I was replacing to learn about the patients I had been assigned. I relied completely on his assessment of each patient, which came in the form of 3 x 5 cards highlighting each patient’s personal information and medical history. I made it a point to memorize everything. Four of my patients were recovering from surgery, and another three patients were awaiting surgery. I would be responsible for presenting these patients during rounds. As instructed, I had arrived early enough to walk into each patient’s room prior to rounds, but all my patients were sleeping. Since I was feeling well-prepared with my 3 x 5 cards, I decided to not wake them up to introduce myself or confirm their history.

When we started rounds, we stood outside each hospital room to discuss the patient prior to introducing ourselves. The chief resident led morning rounds. I could tell Clark was revered by the other interns and residents. I overheard one of the interns say he had already been offered a faculty position at the University, which I later learned was highly unusual this early in a chief resident’s tenure. Clark appeared reserved by nature but seemed to be a thoughtful listener. I was curious about his self-effacing nature given his stature in the eyes of the interns and residents.

A few family members came to the door to listen to our discussions. Clark made a point to tell family members they were welcome to listen and should let him know if they had any questions. Given it was so early in the morning, I was initially surprised by their presence. During rounds, I referenced my colleague’s 3 x 5 card assessments without confirming the accuracy of the information. As I began the presentation of my first patient, a family member immediately corrected my information regarding their family member’s medical history. There was silence from the medical team. By the time I presented my second patient, I realized I had not adequately prepared for morning rounds. I had “dropped the ball” on my first day as a clinician.

After morning rounds, Clark came up to me and asked, “So how do you think morning rounds went?” He was calm and non-judgmental. I replied sheepishly, “I guess I should have come in earlier to do my own examinations and assessments to have a better perspective on each patient.” Clark confirmed my observation by stating, “I guess you know a lot can happen to patients on a surgery service overnight.” I now realize this was my first episode of facilitated self-reflective learning. Clark was forgiving and offered that it takes time to understand the traditions and expectations of clinical practice. I was fortunate to have Clark as my first clinical preceptor. We reviewed the basics of a daily assessment and a competent presentation on rounds. I was grateful and made detailed notes.

I went to a store across the street from the hospital and medical school that evening to buy a new tie. This was a symbolic gesture as Clark had worn a similar tie on rounds that morning. I also purchased an iron to press my shirts and slacks. Though I preferred a relaxed style of dress at this stage of my life, I made sure I appeared neat and professional each day prior to seeing patients. In other words, I dressed each day for my patients and their family. More importantly, I reviewed each patient’s chart in detail, became familiar with their current medical history, and formulated my own assessment and care plan. I also checked each patient’s most recent vital signs and laboratory studies immediately prior to morning rounds. If a study was still pending, I reported this as well as the possible implications of the tests for the patient’s medical care. While I did consult others, I relied on my own final assessment when doing the initial evaluation or presenting patients on rounds. I have shared this story with students and trainees I have worked with as a gentle way to address this important professionalism issue.

I have never forgotten how embarrassed I felt following my first day of clinical practice nor my good fortune to have a role model provide gentle counsel at such a formative period in my medical career. Being the recipient of such generosity from a more senior colleague was an important early lesson in humility. For the remainder of my time on this rotation, I never passed up an opportunity to ask for feedback from Clark following morning rounds or when I was uncertain of my care plan for a particular patient. And I will never forget his parting comment to me: “Great job on your first rotation. You should think about going into surgery.”

Throughout my career as a physician and educator, I have tried to emulate Clark’s example of empathetic teaching and thoughtful mentorship.

Key Concepts

- Discovering your professional identity begins with finding role models who demonstrate the attributes you wish to emulate.

- When you observe exemplars of a positive behavior, you have started the process of assimilating this same positive behavior into your own practice.

- A journal is a useful tool to document positive role models and seminal experiences during your training as your professional identity evolves.

At the beginning of your professional career, identify and observe exemplars who demonstrate attributes worth emulating. Proactive engagement with these role models provides you early insight into specific career paths and highlight best practices in a profession. Role models are easy to identify as they have gained the respect and recognition of their peers with teaching awards, prominent leadership positions, and advanced academic rank. Clark was a perfect role model given his leadership position, professional attributes, and the deserved respect he received from peers.

As you identify role models and observe their positive qualities, you begin to perform a self-assessment of your own personal values and attributes. If your values align well with those you have observed, reflecting forward becomes an important component of your professional identity formation. At an early stage of your career, it is premature to compare yourself to role models or objectively assess your personal strengths and weaknesses. Exemplars who demonstrate these attributes in their profession provide a benchmark for future self-assessment of your professional development.

Prior to the publication of the Flexner Report in the early 1900s and the establishment of formal residency programs, a prominent form of learning for medical school graduates was to participate in preceptorships supervised by more experienced physicians. These designated mentors for new physicians modeled and taught the foundational concepts of professional and clinical practice. While modern residency programs have added structure and consistency to this original form of observational learning, modeling the positive behaviors of exemplars you admire is still an important practice in your professional development.

You can approach your education as an observational learner like a clinical investigator who is opening the door to a future area of research. Clinical researchers often decide to investigate a topic after identifying a clinical problem or reading a case report. A case report or a case series is considered level four evidence per the Oxford Center for Evidence-Based Medicine (OCEBM), but still has value when identifying an interesting diagnosis, treatment, or outcome worthy of investigation. Identification of a professional best practice is simply another form of investigation.

Identifying and modeling professionalism

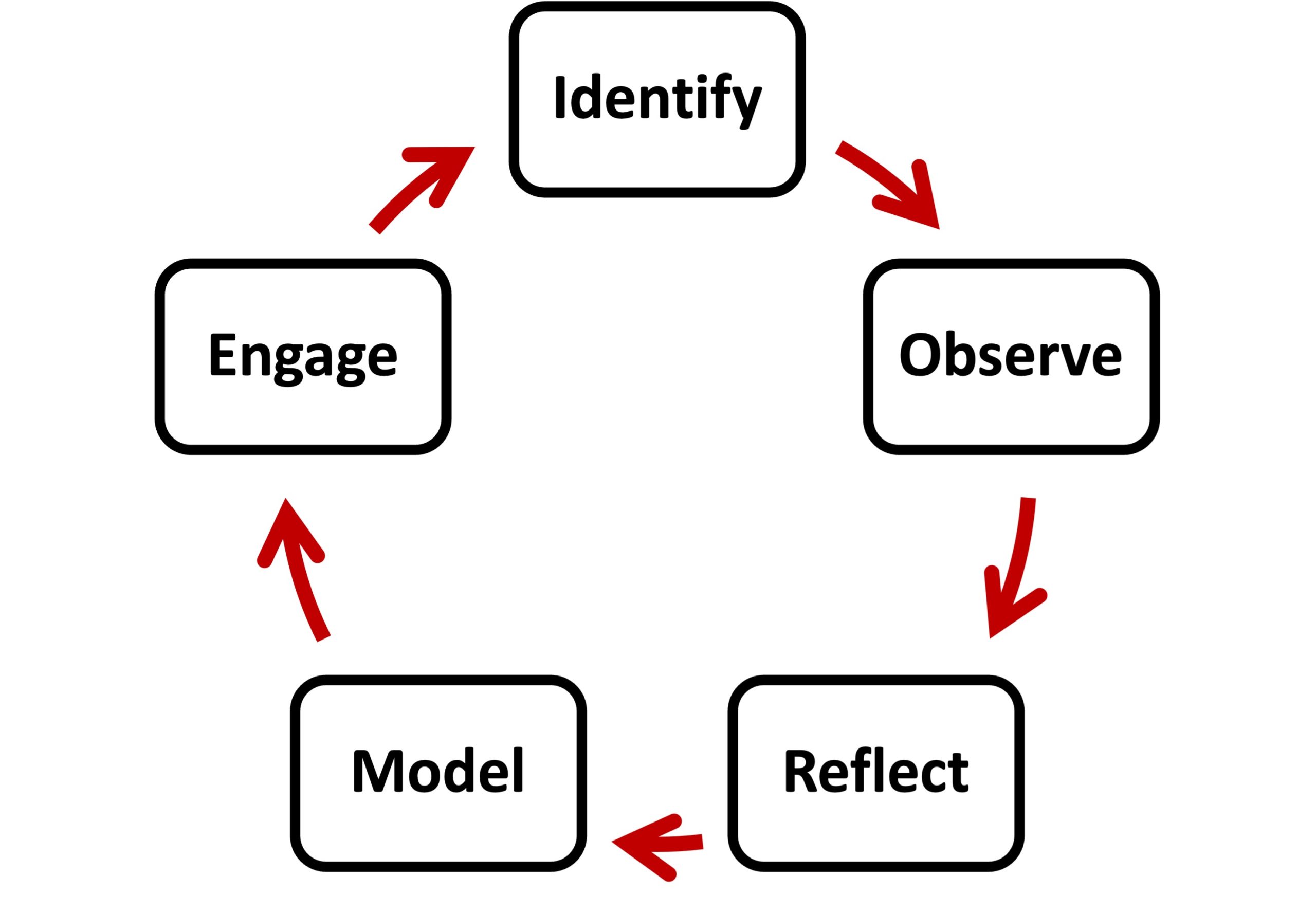

Observational learning starts with identifying a best practice and the exemplar of this positive behavior. Once you identify a role model, you can begin to observe their professional practice, such as how they interact with patients and work as a contributing member of a healthcare team. After a meaningful period of observation, reflect on the observed behavior and contemplate how best to emulate this practice in your future career. The next step is to model this behavior in a professional setting. As a physician in training, you are provided longitudinal relationships with colleagues and patients to replicate a desired professional attribute. At some point, you should engage your role model and colleagues to receive their input so that you can then personalize the practice based on their feedback. A component of engaging colleagues is seeking their counsel to identify other seasoned practitioners to learn from and gain a broader perspective on the desired professional attribute. Though this description makes observational learning sound overly formal, adoption of this practice occurs more naturally in your training and professional career. Young physicians are often reticent to proactively reach out to others for feedback regarding professional issues. I was fortunate to have a senior colleague initiate contact and assist with my professional development. During this rotation, I had the opportunity to observe Clark’s professionalism and teaching as a model for my future career as an educator. In your education and career, commit to becoming proactive in finding professional role models and seeking guidance.

A journal is a useful tool for documenting observational learning episodes and your professional identity formation as your career progresses. When embraced as a living document, a journal will evolve along with your career that can be updated as needed to reflect your evolution as a professional. Personal diaries often contain stories about impactful people and events in a person’s life. Your entries may take the form of descriptive narratives about inspirational people and best practices you have observed pertaining to one or more aspects of professionalism. It is also important to document negative behaviors and people you have observed as another opportunity for self-reflection during your career. Negative behaviors and practices provide very poignant examples of what not to do. Some find it helpful to organize a journal by the stage of your career and the professional issue you wish to document.

If you decide to begin a journal, start with choosing a purpose for your journal. Given this book is about becoming a physician, you could say documenting your medical education and training is a primary goal. As your career matures, consider expanding the scope of your journal to include other categories such as leadership development, evolution of your research, and teaching and mentorship. It is important to choose a platform for your journal that is amenable to your style of recording and reviewing events. Digital instruments such as phones, tablets, and laptop computers are commonly used to document events. Some feel writing down thoughts on paper has value from the standpoint of personalizing the entry as you would a letter you write to a friend. Choosing a familiar format for your journal entries creates a comfortable process for documenting events for future review and self-reflection. Spreadsheets serve to organize your entries in a uniform manner. A commitment to set a schedule for both placing entries in your journal and performing a periodic review optimizes the benefit of maintaining a career journal. Some entries and their respective topics will merit updates as your professional identity evolves. In summary, you optimize the benefit of a career journal when you establish its purpose, choose a user-friendly platform, adopt a uniform template for entries, and commit to a regular schedule of documenting events with designated time for self-reflection.

Suggested Reading

- Horsburgh J, Ippolito K. A skill to be worked at: using social learning theory to explore the process of learning from role models in clinical settings. BMC Med Educ 2018;18(156)1-8. DOI: 10.1186/s12909-018-1251-x

- Park J, Woodrow S, Reznicj R, Beales J, MacRae H. Observation, reflection, and reinforcement: surgery faculty members’ and residents’ perceptions of how they learned professionalism. Acad Med (2010) 85:134-139. DOI: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181c47b25

- Lim A, Hong D, Pisupati A, Ong Y, Yep J, Chong E, Koh Y, Wang M, Tan R, Koh K, Ting J, Lam B, Chiam M, Lee A, Chin A, Fong W, Wijaya L, Tan L, Krishna L. Portfolio use in postgraduate medical education: a systematic scoping review. Postgrad Med J (2023) 99(1174):913-927. DOI: 10.1093/postmj/qgac007