7 Competency

Acquiring knowledge and skill

I was looking forward to starting a new position as an anesthesiologist with a private group in my home state of Arkansas. I had just completed my final handoff as a resident, giving the trauma pager to a junior colleague who would be covering the trauma service and critical care units over the next twenty-four hours for our Department. After wishing me well and giving me a warm embrace the day before, the Department’s secretary had instructed me to leave my pager and office keys on her desk after my night on call since it would be the weekend. Following completion of a long residency, it seemed rather anticlimactic to simply turn off the lights, close the door to the office, and leave the hospital.

I had met with the chairman several months earlier, and he had offered me a faculty position in the Department. I was initially surprised by his offer, which included compliments about my teaching of medical students and more junior residents in the program. I surmised I must be competent if he wanted me to join the faculty. Though the residency had been rigorous with long days and nights on call, especially on my cardiac and critical care rotations, I was satisfied with the quality of my training and felt competent to start the next phase of my career. Looking back as a former residency program director with years of teaching experience, I am amazed how I had simply learned by observing faculty and modeling their practice, often with minimal supervision. My conversations with resident colleagues in other specialties confirmed my training mirrored other residency programs at the time.

I rarely received formal feedback or written evaluations regarding my performance, but I felt I was getting “state-of-the-art” training by doing complicated cases with progressively more responsibility at a well-regarded teaching hospital. I did develop close relationships with a few faculty members who served as confidants as well as role models. During my training, they often provided counsel and shared their perspectives when asked. As I advanced through the residency program, I was given more independence. I assumed things were going well, as it seemed not all residents were given as much autonomy. Towards the end of training, I was allowed to assist more junior residents perform procedures and care for patients in the operating rooms and critical care units. This was especially gratifying and perhaps indicative of their trust in my growing competence.

I like to reflect on how postgraduate medical education has changed since I was a resident in the 1980s. As a program director for a residency program in the twenty-first century, I had a front-row seat learning to navigate the transition to a competency-based model of teaching and assessment based on the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) Core Competencies first published in 2001. The Outcomes Project was intentionally left somewhat aspirational by the ACGME, with an anticipated transition period where training programs were given the directive to experiment and discover how best to incorporate the six core competencies into their curriculums. I think most medical educators concluded that while the core competencies were a good start, we needed more specificity and guidance regarding how to implement competency-based education. A decade later, the ACGME provided training programs with specialty-specific milestones that provided better guidance regarding the trajectory for learning and competency attainment under each of the six core competencies.

During my tenure as program director and then vice chairman for education in the Department, our residents and fellows continued to complain that even with the ACGME milestones, they were not receiving adequate feedback. They claimed these benchmarks were still too abstract without sufficient detail, and therefore, the resultant feedback was not actionable. There is a long history of learning and teaching using the Socratic method in undergraduate and postgraduate medical education. I believe that no other form of teaching and providing feedback will supplant the efficacy of interactive teaching in the clinical environment, including lectures, workshops, or high-fidelity simulation. I now know that much of my growth as a clinician resulted from this form of dynamic teaching and learning that occurred in the clinics, operating rooms, and critical care units during my residency.

Referencing my residency training, I empathize with the current frustrations of students and trainees regarding the quality of their feedback. I believe residents’ primary motivation is to improve performance and overall competency. As educators and learners, we share a responsibility to raise the bar with mutual accountability to improve how we teach, assess, and give feedback. I remain perplexed by the fact that residents and fellows often do not complete their own evaluations of faculty and rotations each academic year. Students, residents, and faculty should continue to work together to innovate and improve teaching and feedback as mutually invested stakeholders. I appreciate how much progress we have already made and remain optimistic that stakeholders are committed to discovering better ways to teach and assess physicians-in-training.

Key Concepts

- Setting personal and professional goals to improve your performance and overall competency is a lifelong endeavor for physicians.

- Dedicated teachers and learners provide feedback to each other to improve physician performance and the quality of training programs.

- As the ACGME and medical specialty boards continue to enhance their competency benchmarks and assessment tools, educators need to independently innovate to establish best practices within their respective training programs.

Undergraduate medical school and postgraduate training program curriculums have transitioned to a competency-based model of medical education in recent years. Prior to the ACGME core competencies and milestones, residency training programs were somewhat like Garrison Keillor’s Prairie Home Companion where at Lake Wobegon “all the children are above average.” If physicians-in-training performed as well as their predecessors in the program, they were declared competent to graduate and qualified to take their respective board certification exams. This “Lake Wobegon phenomenon” does highlight the human tendency to overestimate relative competency in the absence of objective benchmarks.

We now have more objective benchmarks called milestones. Though documentation of the achievement of milestones remains largely observational, serial positive evaluations validate competency attainment, especially when confirmed by more objective demonstrations of knowledge and skill via testing or simulation. Feedback should be specific and constructive as well as actionable, with opportunities provided for learner self-reflection and individualized practice-based learning and improvement, which is one of the ACGME core competencies. The relationship between the preceptor and trainee provides the most immediate and meaningful opportunity to give individual feedback that is both formative and relevant. Training programs are also required to have clinical competency committees chaired by faculty who are not the program director to minimize bias and ensure objectivity in the serial summative assessments of trainee competency at each stage of training. When possible, more than one mode of assessment optimally confirms competency in a specific domain. Multi-modal assessments provide additional opportunities for validation of a skill and confirmation that a specific competency has been achieved. Non-physician assessors are often asked to evaluate professional attributes such as communication skills, teamwork, and leadership.

In Chapter 6, we discussed the importance of identifying mentors to support and guide your professional identity formation. While distinct from a mentor, role models provide another opportunity for your career development, providing perspective and achievable goals on your journey to become a more intentional and highly skilled physician in each professional and clinical competency domain. As you observe role models, perform your own self-assessment, and receive formative feedback pertaining to your own competency attainment, you will often benefit from targeted coaching to assist with the acquisition of a specific competency milestone where you are struggling. Mentors and program directors can assist with assessing areas where a coach can provide guidance and feedback to improve your competency in a specific area. During your training, an important component of any observed entrustable professional activity is seeking and receiving formative feedback from supervising faculty. These debriefings are a good time for self-reflection and to ask for coaching if you feel there is room for improvement.

Pre-dating the ACGME Outcomes Project, Stuart and Hubert Dreyfus described a model of skill acquisition and cognitive function. In 1980, the Dreyfus model of competency attainment listed ascending stages of progress that used the terms novice, advanced beginner, competent, proficient, and expert. Though some have criticized this simplistic model of competency acquisition and others have proposed alternative models, the shared theme of these models is progressive competency attainment leading to expertise. This remains the desired endpoint for professional and clinical training programs. Going beyond expertise, Dreyfus and Dreyfus later updated their model to add another stage of competency called mastery. Physicians who have achieved mastery in their specialty are able to adapt and transform their knowledge and skills to address novel challenges in their clinical field. This stage of competency will remain aspirational for many physicians but is needed to create innovations that will advance science and clinical practice in the future.

Professionalism is considered one of the six core competencies to be taught, modeled, and assessed. The other five core competencies include patient care, medical knowledge, systems-based practice, practice-based learning and improvement, and interpersonal and communication skills. Each core competency has multiple subcategories containing descriptions of progressive advancement of competency from level one to level five. Achievement of a level five competency in each of the core competency domains often requires a physician to have attained independence of practice as well as the ability to lead, supervise, and teach others as a consultant.

Within the professionalism competency domain are specific milestones that describe universal traits a physician should embrace and demonstrate in their chosen field. These milestones address the attitudes and behaviors of resident physicians in their clinical practice. A core concept is physicians should treat every patient with respect and compassion. Training programs now provide their trainees and supervising faculty with a template describing the expected milestones for each level of training.

As the core benchmarks for the ACGME milestones for professionalism are shared by all specialty training programs, I will focus here on the professionalism milestones for internal medicine to highlight the professionalism domains and the progression of competency from level one to five. The first professionalism domain addresses behavior. While a physician who is at level one demonstrates professional behavior in routine situations, a physician who has achieved level five competency is able to coach others when their behavior fails to meet professional expectations. The other professionalism domains encompass ethical principles, accountability and conscientiousness, and knowledge of systemic and individual factors of well-being. In each of these domains, the expectation is that a physician at the level one milestone has basic knowledge and understanding of, and strives to adhere to, these standards in their practice. Physicians at level five competency serve as a consultant assisting others and improving institutional systems in each of these respective domains.

Advancement of knowledge and skill

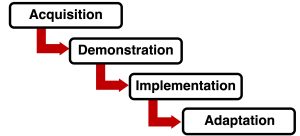

Throughout your career, the acquisition of a new competency assumes you have already learned the foundational knowledge surrounding that skill. There are many formats for acquiring knowledge including seminars, text articles or chapters, and various online forms of learning. Many online learning formats provide a self-assessment survey or quiz at the end of the module to confirm you have acquired the expected knowledge.

While the long-standing tradition of applying acquired knowledge and practicing a clinical skill under the supervision of faculty with more expertise still exists, many workshops now provide simulated environments to learn and where you will provide a demonstration of your competency prior to your implementation of the skill in your practice. Patient safety has driven the growth of both high-fidelity and screen-based simulation. These virtual learning environments provide a less stressful format to build self-confidence and review performance. Simulated learning environments also provide an opportunity to perform rare and high-risk procedures repetitively as well as prepare for any complications that can occur. Forward-thinking practitioners prepare for crises and develop advanced skills even if they rarely use these rescue skills in daily practice. Board certification examinations that utilize written, oral, and objective structured clinical exams (OSCEs) often focus on assessing a physician’s knowledge, skill, adaptability, and judgment in managing both common and rare medical crises.

As your practice becomes more advanced and subspecialized, expect to adapt your current knowledge and skills to novel clinical areas where guidelines do not yet exist. In a future chapter, we explore the need for physicians to continuously review their clinical practice as medical science and technology evolves. Medical schools and postgraduate training programs have started to introduce the concepts of adaptation and innovation as essential for addressing future healthcare challenges.

Suggested Reading

- Ericsson K. Acquisition and maintenance of medical expertise: a perspective from the expert-performance approach with deliberate practice. Acad Med (2015) 90:1471-1486. DOI: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000000939

- Mahant S, Jovcevska V, Wadhwa A. The nature of excellent clinicians at an academic health science center: a qualitative study. Acad Med (2012) 87:1715-1721. DOI: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3182716790

- Cate O, Carraccio C, Damodaran A, Gofton W, Hamstra S, Hart D, Richardson D, Ross S, Schultz K, Warm E, Whelan A, Schumacher D. Entrustment decision making: extending Miller’s pyramid. Acad Med (2021) 96:199-204. DOI: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000003800