12 Ethics

Drawing your line in the sand

Connor was reticent to proceed with preparations for a second transplant and the impending surgical procedure to place a permanent intravenous catheter. He had already experienced years of a disrupted childhood with prolonged hospitalizations for recurrent bouts of rejection. He now required supplemental oxygen at home.

Connor’s parents had parental authority to make medical decisions for Connor, as he was still a minor at the age of sixteen. His parents felt he was too young to make a fully informed medical decision, as did the surgical team. The members of our preoperative team, including his assigned nurse and the nurse practitioner who performed his initial evaluation in our preoperative clinic, appreciated how thoughtful he was as he considered for himself what he wanted based on his personal values and desired future quality of life. They both shared their thoughts with me privately. When I entered the room to discuss the anesthetic and postoperative care with Connor and his parents, Connor stated he did not want to have the procedure or another transplant. Fortunately, our nurse practitioner had forewarned me of his feelings, so I wasn’t taken by surprise. Connor’s mom asked to speak with me privately outside the room. I made sure to make eye contact with Connor to assess his response to this outreach from his mother. He did not make eye contact but quietly looked down at the floor.

By the time we arrived at the family conference room, Connor’s mother was crying. She explained that she and Connor’s father only wanted what was best for Connor, and they felt strongly that he was too young to make a “life or death decision.” I offered that perhaps we should explore Connor’s apprehensions about having the procedure today, and we could have counselors assist with helping Connor discuss his feelings with her and his father. Connor’s mom asserted emphatically, “I am his mother.” And then to my surprise, she asked, “Can’t you just give him something through the IV to knock him out, so he doesn’t know he is going to surgery?” It took me some time to process this statement and her troublesome request. I immediately felt a mix of anger and empathy for Connor’s mother, realizing this was a very difficult position for any parent to be in. What I did know was that Connor should not have surgery today without further exploration of his wish to not have any more procedures, including a second transplant. I stated I was not comfortable with moving forward until we had addressed Connor’s apprehensions, but I understood her desire to do what she thought was best for her son. I suggested she return to the room to confer with Connor and his father. We stayed in the conference room for a few more minutes in silence first. I chose to not offer any further counsel, as I could tell Connor’s mother was deep in thought, contemplating our discussion and how she should proceed. She then said, “I am ready.”

As I looked through the closed glass door, I could see Connor’s mother leading a calm discussion with Connor and his father. While I was standing outside the room, the operating surgeon came up to ask what was going on. Expressing his confusion, he stated, “I am not sure why we are delaying the procedure because I already met with Connor and his parents, and I have consent to proceed with placing the catheter.” As I was about to explain the situation, Connor’s mom came up to both of us to say, “We have some concerns with doing the procedure today without first deciding if Connor would like to have another transplant.” We both stated that surgery could be delayed until everyone was comfortable with moving forward. I was happy that the cancellation of the procedure would not be a point of conflict with the surgical team. I had been prepared to unilaterally delay the procedure to provide time to explore Connor’s concerns if necessary.

I later learned from the transplant coordinator that Connor and his parents reached a mutual decision regarding how to proceed. I did not see Connor or his parents again, but I will always be grateful for the thoughtful advocacy of the nurses I worked with that day to bring Connor’s concerns to my attention. I was similarly appreciative of the surgeon’s respect for a young man’s desire for self-determination even though he was a minor. As a physician, I also learned to not prejudge a parent’s initial reaction to medical counsel, which is rooted in love and in their ultimate desire to prolong the life of their child.

Key Concepts

- The ethical standards of your chosen profession are a foundational component of your professional identity.

- While institutional policies as well as local and federal laws are founded on commonly accepted moral and ethical standards of conduct, you will be required to interpret these rules in ethically complex situations.

- The ethical principles of beneficence, nonmaleficence, autonomy, and justice must be considered when caring for patients and providing informed consent.

You will encounter ethical dilemmas in your medical career. Reflecting on observed role models and best practices that have helped form your own professional identity assists with making principled decisions consistent with accepted ethical standards.

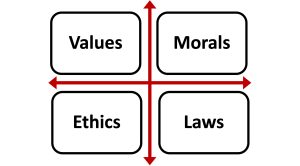

Matrix of principles

Consider how your personal values and morals, the ethics that guide your profession, as well as established laws will impact your practice. Physicians often find themselves conflicted when their own values and morals do not match those of their patients or colleagues.

An individual’s values are unique to the person and inwardly focused. Your personal identity is established earlier than your professional identity and is largely based on your family’s background and your childhood experiences, including friendships and education. In earlier chapters, I have discussed how core values such as empathy are foundational components of your personal identity and evolving professional identity. Empathy with a commitment to understand each patient’s background and values when providing medical care is essential for navigating the ethical challenges associated with being a physician and serving as a patient advocate.

A person’s morals are shared within a community of people and more outwardly focused based on culture, religion, and societal customs. Morals help a person distinguish “right from wrong” or “good from evil.” For individuals with a strong attachment to their family’s background, morals are commonly associated with a country of origin and ethnicity. As a physician, you should be sensitive to both the moral compass of a patient as well as the familial and societal pressures they experience regarding certain personal medical decisions. It is reasonable and prudent in many circumstances to reach out to colleagues or experts familiar with specific moral issues unique to a patient population for their insights and assistance when navigating complex issues.

A patient’s right to self-determination is subject to interpretation of the law by healthcare providers. Familiarize yourself with legal standards and seek legal counsel when patient care issues involve legally complex issues such as emancipated minors, medical directives, power of attorney, or state versus federal jurisdiction. There are few topics as controversial and politically divisive as reproductive rights or the right to autonomous decision-making for a mature and competent adolescent minor. The above story about Connor has become a common dilemma for medical professionals as medical practice has advanced, making more life-prolonging interventions available but with unpredictable outcomes for a patient’s quality of life. Many institutions and hospital systems have established policies and ethics committees to address these complex ethical situations. Established laws are fixed, requiring physicians to comply with very little room for compassionate modification. Physicians act as advocates to assist patients with understanding the applicable laws when providing medical counsel and providing informed

consent.

The topic of providing informed consent regarding medical care that involves some risk to the patient touches upon all the basic principles of ethics. Shared decision-making between the patient, family, and physician, especially involving the care of a sick child, is a demonstration of respect for patient self-determination and commitment to patient-centered care. There are areas of healthcare many find personally challenging to navigate when counseling patients and providing informed consent, such as care surrounding reproductive rights or gender confirmation surgery. While obligated to protect your patient’s right to self-determination when making healthcare decisions, you may not feel comfortable performing an associated procedure based on your personal beliefs. It is possible to fulfill your ethical responsibility to advocate for a patient by making a referral to a colleague and institution willing to provide the respective care. Local and federal laws do limit the care and counsel you are able to provide.

A commitment to the principles of ethical medical practice is a fundamental responsibility of physicians. Modern versions of oaths that medical students often recite during their white coat or commencement ceremonies affirm this commitment. Common themes in many of these oaths include respecting patient confidentiality, avoiding harm, and upholding the integrity of the profession. These pillars of professionalism and ethical medical practice include the principles of beneficence, nonmaleficence, autonomy, and justice. It should be noted that these themes and core principles are shared with other professions.

Beneficence simply defined means that physicians act to benefit their patients. It is the most positive and altruistic of the four ethical principles consistent with the core reason physicians decide to pursue a career in medicine. When most broadly interpreted, beneficence also obligates a physician to maintain an acceptable level of competency with a commitment to best practices as the standard of care for their patients. It also implies that physicians will consult others and refer patients to colleagues if their expertise is not the best standard of care available. A modern version of the Hippocratic oath written by Louis Lasagna in 1964 states, “I will not be ashamed to say, ‘I know not,’ nor will I fail to call in my colleagues when the skills of another are needed for a patient’s recovery.” This is common in the emergency care of a trauma patient who may have a life-threatening injury that requires stabilization prior to transport to a higher-level trauma center with more advanced technology and clinical subspecialists. Physicians often struggle with their decision to transfer an unstable patient when the relative risk of the transfer must be factored into the benefit of a patient receiving care at a higher-level facility.

The principle of nonmaleficence, as highlighted in the traditional version of the Hippocratic oath, “first, do no harm” obligates physicians to weigh the risks their care poses of causing injury or having a negative impact on a patient’s quality of life. As in the case of Connor, advances in medical science have given physicians the tools to prolong life without fully knowing what that quality of life will be. This principle becomes challenging for physicians when counseling patients with incurable conditions such as terminable cancers, progressive conditions such as neuromuscular disorders, or organ failure that is amenable to transplantation. In this regard, physicians should be sensitive to a patient’s personal values and morals as well as the external influences they face, such as from family. In recent years, physicians have had to balance the risks to patients of prescribing opioids with a desire to treat painful conditions. There are few instances when doing a thoughtful risk-benefit analysis is more important to avoid harm than when considering the long-term effects of prescribing opioids, including drug dependence and addiction. It is notable that many states now require physicians to participate in continuing medical education associated with best practices and the risks attached to prescribing opioids.

Autonomy is a basic right of all patients. Physicians have a primary responsibility to act as advocates to ensure their patients are fully informed and have self-determination when making medical decisions impacting their lives. The principle of autonomy presents challenges when a patient’s wishes for their medical care conflict with accepted standards of care or the law. Cases such as Connor’s prove challenging when minors may not have full legal independence but still deserve some degree of self-determination. An important component of providing informed consent with a discussion of the risks and benefits of treatment options is clarifying the relevant ethical and legal issues for patients and families.

Patient autonomy to choose to not have lifesaving or life-extending interventions challenges a physician who thinks a decision is premature or the patient does not fully understand the nuances surrounding the “do not resuscitate” (DNR) status. For example, a physician is frequently able to rescue a patient who experiences a reversible adverse event such as an anaphylactic reaction to a medication. In the case of advanced directives, it is sometimes important for the physician to cover with their patient specific clinical scenarios to gain a better understanding of the patient’s wishes. This type of comprehensive discussion enhances a patient’s understanding of their DNR status with an opportunity to ask follow-up questions.

A patient’s right to confidentiality must also be protected by caregivers. In fact, there are strict rules governing patient confidentiality. The Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) Privacy Rule is a national standard designed to protect a patient’s medical records and other identifiable health information. This rule applies to all healthcare providers, hospitals and clinics, and health plans. There are some exceptions to this rule that often involve matters of protecting public health and safety, such as reporting injuries associated with a violent act to law enforcement, sexually transmitted diseases to partners, and broader infectious diseases in the context of an epidemic to health authorities.

All patients have the right to fair access to medical care and available treatment, as highlighted by the ethical principle of justice. It is beyond the scope of this discussion on ethics to cover the politics and funding of healthcare to all patients in every country. For many physicians, proactively engaging local leadership and becoming involved in national organizations and initiatives as ways to improve access to healthcare are personally rewarding because such activities are consistent with the ethical principle of justice. Physicians must also recognize that the history of human abuse in research gives certain patient populations added concern when they are presented with newer therapies or asked to participate in a study of a novel drug therapy or treatment protocol.

The discovery of physician complicity in Nazi atrocities against the Jewish people and other prisoners that included human experimentation serves as a poignant reminder of the history of human abuse attached to research. Following World War II, the World Medical Association adopted the Declaration of Geneva, which included the following statements:

I WILL RESPECT the autonomy and dignity of my patient.

I WILL MAINTAIN the utmost respect for human life.

I WILL NOT PERMIT considerations of age, disease or disability, creed, ethnic origin, gender, nationality, political affiliation, race, sexual orientation, social standing or any other factor to intervene between my duty and my patient.

I WILL NOT USE my medical knowledge to violate human rights and civil liberties, even under threat.

In this country, the U.S. Public Health Service Untreated Syphilis Study at Tuskegee was conducted beginning in 1932. It was designed to study the natural course of untreated syphilis in black males. Researchers did not obtain informed consent from participants, and they did not offer medical treatment when it became available during the study. Many participants suffered severe sequelae from untreated syphilis, including death. Awareness of the Tuskegee Syphilis Study may explain the underrepresentation of racial minorities in past research studies. The National Institutes of Health (NIH) now mandates the inclusion of minorities in population-based studies. There is evidence that acknowledgements of this suffering as well as a formal U.S. presidential apology for the Tuskegee Study have positively impacted the willingness of minority populations to participate in future research studies. Informed consent with full disclosure of the risks and benefits of study participation is now a fundamental tenet of enrolling participants in research protocols. The NIH guiding principles for ethical research provides researchers with guidelines for conducting research, enrolling participants, and providing informed consent.

Ethical medical practice obligates physicians to provide the best medical care available for their patients, consistent with the principles of beneficence, nonmaleficence, patient autonomy, and justice.

Suggested Reading

- Varkey B. Principles of clinical ethics and their application to practice. Med Princ Pract (2021) 30:17-28. DOI: 10.1159/000509119

- Scopetti M, Santurro A, Gatto V, Padovano M, Manetti F, D’Errico S, Fineschi V. Information, sharing, and self-determination: understanding the current challenges for the improvement of pediatric pathways. Front Pediatr (2020) 8:371. DOI: 10.3389/fped.2020.00371

- Katz R, Kegeles S, Kressin N, Green B, James S, Wang M, Russell S, Claudio C. Awareness of the Tuskegee Syphilis Study and the US presidential apology and their influence on minority participation in biomedical research. Am J Public Health (2008) 98:1137-1142 DOI: 10.2105/AJPH.2006.100131