8 Curiosity

Learning like Socrates

I remember the first time I was scheduled to work with Trent, a second-year anesthesiology resident. As was customary, Trent called me the night before we were scheduled to work together in the operating room to discuss our patients for the next day. This was his first pediatric rotation at our children’s hospital. He had already completed six months of clinical rotations in the operating rooms and critical care units at our adult hospital following the completion of his one-year internship there.

When Trent presented our first patient, appropriately highlighting the child’s medical history and laboratory studies and the scheduled procedure, I asked a few follow-up questions. It was important to explore some added issues, including the child’s past surgical history prior to Trent presenting his anesthetic plan. He was able to answer each question. I then waited for him to present his proposed plan to care for this child, but there was silence. When I asked Trent how he planned to proceed with the anesthetic, he responded by saying, “Whatever you want to do.” This surprised me as I had assumed he would be prepared to discuss a perioperative care plan, including premedication, induction, airway management, and maintenance of anesthesia, as well as his plan for postoperative care. For children with complicated medical histories scheduled for complex procedures, it is expected that a resident will also anticipate the complications that could occur and discuss risk mitigation strategies.

I was disappointed that Trent had progressed this far in his training and had not adopted a more proactive approach to the risk assessment and medical care of his patients. I was also disheartened that previous faculty had apparently been prescriptive in their instruction and not encouraged Trent to take more ownership of his cases. Sadly, I had worked with other residents and fellows over the years who were also more comfortable with the “just tell me what to do” approach, especially if they had a recent history of working with overly directive and rigid faculty.

I gave Trent a bit of latitude knowing that early in training residents are deferent to their faculty. I also remembered my own naivety and uncertainty at the beginning of my medical school rotations and subsequent residency decades earlier, which helped to temper my initial reaction. I decided it would be better to slowly raise the bar for Trent over the course of his first pediatric rotation. Trent probably sensed my frustration with his lack of an anesthetic plan, explaining that he had never cared for a pediatric patient. After empathizing with his apprehension, I encouraged Trent to set a personal goal to independently present anesthetic plans and consider possible complications for each child during our case discussions by the end of the rotation. I shared that he should feel comfortable disclosing when he was uncertain about a plan and that he was free to ask questions as we would decide on the final care plan together.

When a resident had not embraced the Socratic method of interactive learning, I often challenged them to provide topics for discussion the next day pertaining to the medical condition or management of our first patient that we had not already discussed. I hoped Trent would adopt a more proactive attitude the next time he presented a case with this type of encouragement. Though a bit puzzled by my request, Trent accepted the challenge. The following day, he asked several questions that were very insightful and relevant to the anesthetic management. In fact, he challenged our induction strategy and asked if we should consider another given the child’s compromised cardiac status. Though not practical for this child, it was reasonable to suggest and discuss an alternative strategy. I was impressed. One of my most rewarding moments as a faculty member has been seeing a resident or fellow overcome their innate apprehensions and become an engaged learner, challenging me to teach them and explore the limits of their knowledge.

I had the good fortune to work with Trent several more times during his first pediatric rotation. He soon became more proactive in presenting his patients and proposing anesthetic plans over the month. He also stumped me several times with probing questions. I decided to take a few minutes to debrief Trent at the end of each day in the operating room. Novel experiences can be particularly stressful early in a resident’s training. A typical debriefing started with asking him how he thought the day went. Most residents are self-deprecating and overly critical of their performance. After providing some feedback and encouragement, I would ask Trent to identify an area for improvement. I also asked him to choose a topic he would like to explore further. We would then identify the best resource for learning such as a review article or text chapter. I closed our debriefings by asking if there was anything I could do to improve my teaching. I wanted to communicate to Trent that we are colleagues still on a learning curve. Though he rarely offered a suggestion for improvement, I would sometimes point out an area I felt I could have done better.

On the last day of his rotation, Trent told me he was looking forward to his next pediatric rotation and working together again. He also asked if we could meet sometime to discuss a pediatric fellowship. We have kept in touch over the years. Trent is now a pediatric anesthesiologist at an academic children’s hospital where he teaches medical students and residents. I am certain he still embraces the Socratic method of teaching.

Key Concepts

- The Socratic method of teaching provides a dynamic learning opportunity for participants when a safe environment is maintained by educators.

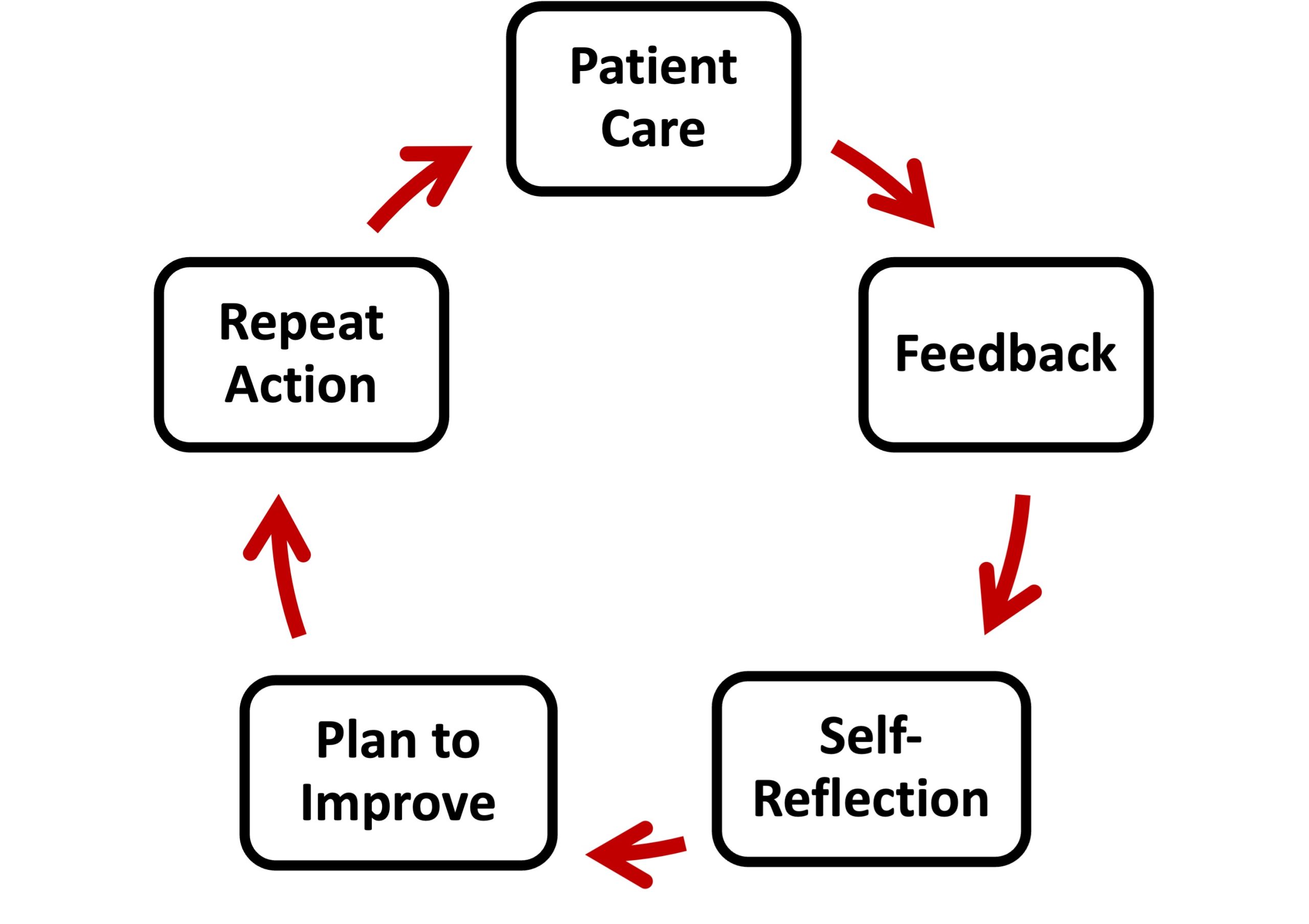

- Practice-based learning and improvement is a lifelong pursuit nurtured by self-reflection and identifying areas for improvement based on feedback and performance data.

- Developing metacognitive skills is important for physician learning and decision-making.

Medical schools are creating faculty teaching fellowships as well as formal institutes to foster the development of faculty educators, which highlights the commitment of institutions to innovate and better educate the next generation of physicians. While there are many novel teaching paradigms, the Socratic method of teaching remains a longstanding tradition in medical education, serving as a foundational component of bedside teaching and problem-based learning formats. When the teacher challenges the student and the student challenges the teacher, it provides a dynamic learning environment where you learn to question conventional wisdom, think deeply, and discover the best evidence-based solution. Problem-identifiers become problem-solvers and critical thinkers. Socrates stated, “The only true wisdom is in knowing you know nothing.” While Socrates may seem rather harsh and absolute with this assessment of knowledge and wisdom, you should remain cognizant of your knowledge deficits as you continue to learn at each stage of your career. And as you do, remember that practice-based learning and improvement (PBLI) is an important form of continuing education throughout your medical career.

It is essential that educators and programs maintain a safe environment in clinical settings for the Socratic method of instruction to avoid creating an environment where learners fear being humiliated without personal benefit. The “pimping” phenomenon occurs when learners feel they are being demeaned and harassed by probing questions that test the limits of their knowledge. To create a safe environment, educators can introduce an interactive teaching session with a disclosure that participants are not expected to answer every question but are encouraged to attempt to discuss topics to the best of their ability and challenge themselves to expand their knowledge and understanding of a topic. Participants are encouraged to ask questions of faculty and colleagues to reinforce the shared nature of interactive learning sessions.

Practice-based learning and improvement (PBLI)

When delivering patient care, proactively seek feedback from supervising faculty and colleagues. Multi-modal feedback from a diverse set of colleagues provides especially formative insights regarding professionalism and communication skills. These unique perspectives are particularly useful for self-reflection and developing a comprehensive plan for improvement. Once you repeat an action, you can reassess your performance with added perspective. Physicians who are proactive and engage colleagues in their learning are respected by their peers.

The Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) competency milestones for PBLI in internal medicine embrace the concept of proactive and self-reflective learning. The PBLI milestone for evidenced-based and informed practice states that at level two a physician “articulates clinical questions and elicits patient preferences and values to guide evidence-based care.” Before visiting any patients on morning rounds, envision a resident discussing the care for a patient to explore both what is the most appropriate treatment and what would be a patient’s preferences for a prescribed therapy. The faculty member leading these rounds, who has probably achieved level five competency, is a physician who “coaches others to critically appraise and apply evidence to patient care.” Supervising faculty members routinely facilitate a discussion among the team regarding recent scientific evidence and practice guidelines to reach a consensus regarding the best treatment recommendation prior to the team entering the patient’s room. As a consultant physician and educator, you are expected to be on the forefront of examining and incorporating best practices into your clinical practice and teaching.

The PBLI milestone for reflective practice and commitment to personal growth expects a physician to “accept responsibility for personal and professional development by establishing goals” and “identify the factors that contribute to gaps between ideal and actual performance with guidance.” At a minimum, you are expected to become a self-reflective learner as a physician at level one. As I have discussed in previous chapters, it is necessary for physicians to acquire the appropriate knowledge, experience, and judgment to become compassionate and highly competent practitioners. As an attending at level five, you should be able to “coach others on reflective practice” and “use performance data to measure the effectiveness of an individualized learning plan and when necessary, improve it.” Level five experts can also serve as counselors to junior colleagues by assisting with their career development.

Entrustable professional activities (EPAs) are defined as professional tasks that can be observed to assess a physician’s competency. Undergraduate and postgraduate education programs continue to identify the core tasks and behaviors to be observed and assessed prior to progressing to the next stage of training. For example, a medical student must be able to take a complete medical history and do a basic physical exam prior to beginning a residency program. An internal medicine resident must be able to initiate and complete an evaluation of a patient presenting with hypertension prior to beginning a cardiology fellowship. A cardiology fellow must be able to conduct a complete work-up, including invasive and noninvasive studies on a wide range of cardiac conditions prior to practicing independently as a cardiologist. One debate surrounds which tasks are required and which remain aspirational for physicians prior to advancing to the next stage of their training and career. For many competencies, the level five milestones within each core competency are achieved during fellowship or following completion of training.

Practicing physicians who have completed training are required to document continued competency via EPAs such as participation in quality improvement programs or peer assessments of competency in fundamental aspects of their practice. Many of the specialty maintenance of certification requirements focus on a physician’s self-assessment of their practice. An overarching theme of future competency assessments focuses on a physician’s ability to work as a member of a multidisciplinary team and improve the quality of care in the institutions where they practice.

A desired endpoint of becoming a competent practitioner is gaining the trust of colleagues who will depend on you to serve as a consultant with the self-confidence to make difficult decisions and provide reliable counsel. Self-awareness of your limitations and cognitive biases is an important component of developing sound judgement. A definition of metacognition is an awareness and understanding of how you think and learn. Learning about the conscious and unconscious processes that surround your cognition helps inform your future learning and decision-making. Continued reassessment of your knowledge deficits and identification of the most effective tools for improving your knowledge acquisition assists with efficient and effective attainment of new skills.

The dual process theory of cognition describes two systems of thinking. The first system is the more automatic. This system of thinking tends to be fast, reactive, and susceptible to emotions. In some cases, it in irrational and subject to biases. In a later chapter, we will discuss the common cognitive biases that negatively impact physician decision-making and ability to provide objective informed consent to patients. There are several mental strategies to address this more impulsive form of cognition, such as taking time prior to answering a question to process your thoughts. Asking follow-up questions and seeking further clarification in a discussion gives you the opportunity to pause, reflect, and achieve a deeper understanding of the subject matter. This a foundational principle of the Socratic method of teaching and learning.

The second cognitive system is associated with thoughtful consideration of the topic being discussed as well as sound decision-making. This type of reflective or analytical thinking is slower and more objective. It is typical of a self-confident learner and consultant. The development of metacognitive skills enables you to become more self-reflective, learn how best to apply knowledge and novel concepts to your practice, and problem-solve. A core tenet within the PBLI competency domain is a commitment to continuous self-assessment of professional and clinical competency with an increased ability to improve your performance based on clinical outcome data and other forms of feedback.

Recognizing these models of cognition and your own tendencies can be transformative in your education and professional interactions with colleagues, as it can empower you to be more intentional in your thinking and actions. Remember, Socrates’ motto was “know thyself.”

Suggested Reading

- Stoddard H, O’Dell D. Would Socrates have actually used the “Socratic method” for clinical teaching? J Gen Int Med (2016) 31:1092-1096. DOI: 10.1007/s11606-016-3722-2

- Abou-Hanna J, Owens S, Kinnucan J, Mian S, Kolars J. Resuscitating the Socratic method: student and faculty perspectives on posing probing questions during clinical teaching. Acad Med (2021) 96:133-117. DOI: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000003580

- Carraccio C, Englander R, Gihooly J, Mink R, Hofkosh D, Barone M, Holmboe E. Building a framework of entrustable professional activities, supported by competencies and milestones, to bridge the educational Continuum. Acad Med (2017) 92:324-330. DOI: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000001141