9 Socialization

Nurturing professional relationships

I love working with a medical student and a resident together in the operating room or clinic. I especially enjoy observing the interactions between the resident and medical student. There is no better way for a resident to reaffirm their own professional identity than to share their evolving journey of self-discovery with someone who is still early in their education and career. I have found senior residents and fellows are much more perceptive than me in determining why a medical student may be struggling with learning a particular concept or acquiring a basic skill. Since residents have recently been in the same stage of their career, they possess relatable insights regarding the best method to facilitate a student’s learning.

I remember listening with admiration as one of our residents was sharing her own story to a medical student about how she decided to choose a specialty and then a training program. This medical student was struggling with evaluating his options for his fourth-year electives to determine which rotations would best assist with his career decision. While I would also share an occasional anecdote, I was respectful of my resident’s ownership and lead in this mentorship session. During my career as a faculty member, residency program director, and vice chairman for education, I have learned to appreciate how well peers can provide thoughtful counsel to each other. Peer relationships can be an especially effective and impactful resource for career development in training programs given the bond and trust residents develop with each other over the course of their training.

On our Department’s inaugural rotation to Central America, two chief residents accompanied me. I served as their supervising faculty member, anticipating that I would also need to perform a comprehensive assessment of the feasibility of establishing and maintaining a long-term relationship at the hospital we were visiting. My directive to our chief residents was to get to know their peer residents, understand their perspective and unique challenges, and look for possible opportunities to collaborate on mutually beneficial education and quality improvement projects in the future.

Our first few days in the hospital were devoted to observing the residents’ clinical practice and professional interactions. We were also interested in assessing how they learned. We were immediately taken by how welcoming everyone we met was. We were welcomed by peers with a kiss on the cheek, and it was endearing to observe residents greeting each other in a similar fashion. We soon became comfortable with this social and professional custom.

We observed the strong peer relationships and support among the residents, with senior residents teaching and supervising junior residents. Their chief resident took point by providing directions to the senior residents. As most of the faculty were engaged in their own private practices, we realized that most of the teaching was provided by the chief resident and designated senior residents. These residents were very interested in the responsibilities of our chief residents. They also seemed curious about my constant presence in the clinical areas. Our chief residents quickly bonded with residents at the hospital. I overheard many conversations comparing the training in the United States to their country. These residents were very interested in the traditions surrounding faculty supervision and faculty teaching in the operating rooms and critical care units in our Department.

I discussed the importance of observational learning to identify best practices pertaining to professionalism in Chapter 3. This same model of learning also applies to observing clinical practices that provide opportunities for intervention and improvement. Our chief residents noted that many of the practices we observed at their hospital were not up to date, notwithstanding the limitations of their equipment. Many of their ventilators had the capability to use multiple modes of ventilation for infants and children but were not being utilized by residents and faculty. Hand ventilation was often used for infants and small children, leaving physicians unable to multitask and complete other essential lifesaving actions such as administering resuscitation medications and performing critical procedures.

The residents were anxious to learn new techniques, so we felt they would be receptive to lectures and workshops. Our chief residents decided that providing a workshop where residents could learn about different modes of ventilation for neonates and infants in the operating room and then practice as a group could be impactful for improving their clinical practice. While creating this workshop was a leap of faith, our chief residents had already established relationships and developed credibility with their resident colleagues in another country. This trust would be necessary to engage these residents in a novel interactive learning session. While the Socratic method of teaching and learning is common in our country, trainees from other countries are often uncomfortable learning in front of their peers for fear of being embarrassed. I was surprised and gratified to see so many of their residents raise their hands and volunteer to participate in this workshop.

Over the course of a couple of weeks, the residents became comfortable using alternative modes of mechanical ventilation for infants and children in their operating rooms. They also began asking questions about other aspects of pediatric practice as they explored the limitations of the learned ventilation strategies. This relatively simple workshop was transformative to their education and clinical practice. I attribute the success of our inaugural rotation to the peer relationships and trust our residents had developed with the residents from another country over the course of just a few days.

I have found our residents were sometimes the first to reach out and share that a fellow resident may be struggling academically or professionally in our program. This outreach with the added input of the chief residents was often accompanied by a thoughtful recommendation for assisting the resident, such as a change in their rotation schedule or suggestions for faculty who were particularly adept at working with residents experiencing a similar difficulty. I often approached our chief residents when assessing a struggling resident or faculty member, or any troubling aspect of our curriculum to gain further insight and better understand a problem. I also gained insight about faculty teaching and professionalism as well as how the hospital functioned by meeting with our chief residents regularly over the years. Our resident forums were especially helpful in learning about the challenges residents face in their training. Our residents’ presentation of a problem was frequently accompanied by thoughtful insights and recommendations for improvement.

While we have more diverse residency and fellowship programs, the strong bond and camaraderie formed by our residents during their training has been unwavering, serving as a formative component of each resident’s professional identity formation. I truly believe a physician’s desire to cultivate meaningful professional relationships with colleagues over the course of their career begins early in their education and training.

Key Concepts

- Peers that become trusted confidants provide a reliable support system as you experience professional and academic challenges together.

- You benefit from meaningful professional relationships when you appreciate the distinctiveness of each colleague you work with.

- Establishing new relationships with colleagues from diverse backgrounds and viewpoints enhances your professional identity and informs your future career decisions.

Finding trusted and supportive colleagues during a long continuum of education and training is essential to your development as a physician and professional. Seek colleagues who value friendships with people from diverse backgrounds and are similarly motivated to discover alternative perspectives that enhance their professional development and understanding of others. Embracing diverse relationships and ideas is a central component of your career development.

Friends and colleagues serve as confidants for sharing aspirations and a sounding board for discussing new opportunities. You grow professionally as you listen to, empathize with, and provide counsel to close friends when they share their personal thoughts and career ambitions. Discovering your own professional identity can be more gratifying and affirming if it is a shared experience with colleagues.

Social influences in training programs

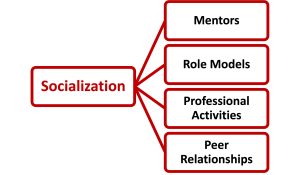

There is a concept in professional development called socialization. In simplest terms, socialization is the process of learning that embraces a variety of professional and societal influences commonly found in academic environments, including mentors, role models, professional activities, and peer relationships. For physicians-in-training, this occurs during their residencies and fellowships at academic institutions, inclusive of rotations in hospitals and clinics. Undergraduate medical and postgraduate training programs provide a formal and optimal environment to grow professionally.

Your personal identity and core values are formed early in life based on your childhood experiences, education, and personal relationships, as well as your family and cultural background. While your personal identity is well-developed by the time you begin your medical training, diverse experiences and relationships provide added context and influence your professional identity formation. You will benefit from actively reflecting on past experiences to better understand novel professional experiences within a new social context.

You benefit professionally by participating in entrustable professional activities during your clinical training and participating in a variety of academic activities, including interactive learning sessions and multidisciplinary conferences such as Grand Rounds or Morbidity and Mortality conferences. Experiencing morally and ethically complex clinical situations in a professional setting inevitably challenges some of your long-held personal values and beliefs. As you learn to navigate these challenges in a larger social context where you are exposed to a variety of contrary beliefs and perspectives, you can grow professionally, reaffirm many of your core values, and socialize your evolving professional identity with others. Learning to defend your principles in a setting of diverse values and opinions is important for the development of self-confidence as you also learn to respect alternative points of view.

The Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) supports the concept of socialization as a way to enhance the education and career development of residents and improve residency programs. Programs work to provide opportunities for residents and fellows to acquire the skills needed to support colleagues in attaining competency related to the milestones within the six ACGME core competencies. For example, the internal medicine level five milestone for the patient care competency domain and clinical reasoning states that a physician “coaches others to develop prioritized differential diagnoses in complex patient presentations” and “models how to recognize errors and reflect upon one’s own clinical reasoning.” The level five milestone for the professionalism domain and professional behavior states that a physician “coaches others when their behavior fails to meet professional expectations.” As residents and fellows near the end of their training continuums, it is an expectation that programs provide opportunities for their trainees to coach and model the attributes of a competent consultant physician for more junior colleagues.

In earlier chapters, I addressed the topic of identifying role models and their importance in the development of your professional identity and career planning. As your training progresses, you receive more responsibility and face increasingly complex professional situations. Trusted mentors and colleagues assist you with remaining uncertainties and provide you a seasoned perspective, especially when you experience self-doubt. An important component of socialization in the development of your professional identity is seeking periodic counsel from peers and mentors, and identifying role models whose attributes you wish to emulate.

If you acknowledge the importance of developing professional relationships early in your career and remain open-minded, your professional development will be enhanced by colleagues from diverse backgrounds and different perspectives. I have also discussed the importance of respecting people from different cultural backgrounds and perspectives as you develop your own professional identity. By supporting friends as they experience personal and professional challenges, you become more empathetic and compassionate. Professional colleagues who become close and encouraging friends provide a support system in times of hardship.

Staying connected to family and childhood friends provides you access to another important source of encouragement when you experience self-doubt about your career. In turn, you provide family and friends the opportunity to become invested in your career and happiness. Keeping your whole support system, including family, colleagues, and mentors updated regarding your career provides opportunities for shared perspectives and continued support.

Suggested Reading

- Cruess R, Cruess S, Boudreau D, Snell L, Steinert Y. A schematic representation of the professional identity formation and socialization of medical students and residents: a guide for medical educators. Acad Med (2015) 90:718-725. DOI:10.1097/ACM.0000000000000700

- Cruess R, Cruess S, Steinert Y. Medicine as a community of practice: implications for medical education. Acad Med (2018) 93:185-191. DOI: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000001826

- Wald H. Professional identity (trans)formation in medical education: reflection, relationship, resilience. Acad Med (2015) 90:701-706. DOI: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000000731