Chapter 1: Geospatial Thinking

Adapted from Campbell and Rosenfeld

Everything happens somewhere, that somewhere is known as “place.” Examining where a thing happens may help us understand:

- What happened

- When it happened

- How it happened

- Why it happened

- The relationship and impact of a phenomenon and place

- What/where something might happen next.

Whether it is an outbreak of a highly contagious disease, the discovery of a new frog species, the path of a deadly tornado, or the nearest location of a supermarket, knowing something about where things happen is important to understanding and relating to society, nature, our locality, and to the world at large.

Functions of (Geo)spatial Thinking

The National Research Council describes spatial thinking as the constructive amalgam of three elements: concepts of space, tools of representation, and processes of reasoning. And its functions are defined as:

- Description: capturing, preserving, and conveying the appearances and relationships among objects

- Analysis: function, enabling an understanding of the structure of objects

- Inference: generating arguments about spatial questions.

(National Research Council et al. 2006)

We might reframe these functions for geospatial thinking

- Descriptive: capturing and curating place and objects within it

- Analytical: understanding the structure and relationships of objects primarily in place, and in relationship to time, and context.

- Inferential: generating questions and answers about place and the objects within it.

- Communicative: creating purposeful, clean, and informative visual descriptions of place.

Asking Geospatial Questions

A geographic question seeks to understand place and how we relate to it. Such questions can be simple with a local focus (e.g., “Which way is the nearest hospital?”) or more complex, with a more global perspective (e.g., “How is urbanization impacting biodiversity hotspots around the world?”). The thread that unifies such questions is geography. For instance, the question of “where?” is an essential part of the questions “Where is the nearest hospital?” and “Where are the biodiversity hotspots in relation to cities?” Being able to articulate questions clearly and to break them into manageable pieces are very valuable for geospatial problem solving.

John Snow’s Cholera Map is the most cited and earliest example of spatial thinking impacting public health. Cholera was considered a respiratory disease, but as a doctor particularly interested in the developing field of anesthesiology, John Snow, and his colleagues felt the symptoms Cholera victims displayed did not appear to be respiratory in nature. They believed it was a waterborne illness. Snow focused on Central London (concept of space) and mapped (tools of representation) the area including the wells and added incidents of Cholera deaths. Based on his map, it appeared the cholera epidemic’s epicenter was the Broad Street well (process of reasoning).

Learning how to ask an effective question takes practice and is often more difficult than finding the answer itself. However, when we ask an effective question, problems are more easily solved and our understanding of the world is improved. There are five general types of geographic questions that we can ask. Each type of question is listed here and is also followed by a few examples (Nyerges 1991).

Questions about geographic location:

- Where is it?

- Why is it here or there?

- How much of it is here or there?

Questions about geographic distribution:

- Is it distributed locally or globally?

- Is it spatially clustered or dispersed?

- Where are the boundaries?

Questions about geographic association (proximity):

- What else is near it?

- What else occurs with it?

- What is absent in its presence?

Questions about geographic interaction (relationships):

- Is it linked to something else?

- What is the nature of this association?

- How much interaction occurs between the locations?

Questions about geographic change:

- Has it always been here?

- How has it changed over time and space?

- What causes its diffusion or contraction?

Why Don’t We Just Call It Geography?

Geospatial thinking is an interdisciplinary descendant of geography. Classic geography focused on understanding the shape of the earth and the location of things. As geography evolved over centuries from a purely descriptive and cartographic endeavor to a research-focused field, it became more concerned with complex spatial relationships. However, it’s the applied interdisciplinarity which emerged in the mid-twentieth century that really helped the concept of geospatial thinking to take shape. The table below provides geographic topics which are frequently asked by experts from various areas of expertise, industries, and professions.

|

Field |

Example Place Topics |

|---|---|

|

Urban planners, traffic engineers, demographers |

Understanding the commuting patterns between cities and suburbs (geographic interaction). |

|

Biologists and botanists |

Why one animal or plant species flourishes in one place and not another (geographic location/distribution). |

|

Epidemiologists and public health |

Where disease outbreaks occur and how, why, and where they spread (geographic change/interaction/location |

|

Climatologists |

The causes and consequences of global warming |

|

Epidemiologists |

Locating ground zero of a virulent disease outbreak |

|

Archaeologists |

Reconstructing an ancient site |

|

Political consultants |

Developing campaign strategies |

The Power and Responsibility of Mapping

Mapping is a way to “write the world” and therefore is a kind of representation. The art and science of creating maps is known as cartography. With cartographic representation, especially in trying to represent a 3D earth on a 2D surface, comes distortion, which shapes our geographical knowledge of the world and affects our perceptions of place. Maps have power. Historically, maps were created for and by those with political power. Maps were used to demarcate and claim ownership of land; a means of showing everyone that one has planted their proverbial flag to claim possession. As such, maps have an air of authority and of being “official” and “true.” But all maps are made for specific purposes and can have both accidental and purposeful lies included. The accidental, small white lies of a map most often have to do with the creation of a representation and generalization.

Maps have scale and will show a larger geographic area than the size of the paper they are printed upon. Because the map is not at a 1:1 scale to the world, objects must be simplified or generalized to not be overly cluttered by the infinite complexity of the world. What is shown, and just as importantly not shown, are choices made by the cartographer. A map might show the locations of important socioeconomic features, like schools and mines, but not show features like landfills or prisons. Labeling maps and adding toponyms (names of places) is also a representative practice and reminds us of the power involved in the act of representing. Labels assign meaning to the area mapped here from the mapmaker’s perspective, but do not necessarily reflect the meaning the land has for others. Colonial era maps often used the label terra nullius, a Latin term meaning “nobody’s land” or “empty land.” Maps with this label played a role in justifying colonialism, as colonizers used the supposed reality, as marked on a reliable map, that land was unoccupied and therefore up for grabs. Labels like this ignore and silence the presence of indigenous people and meanings of land held by non-mapmakers.

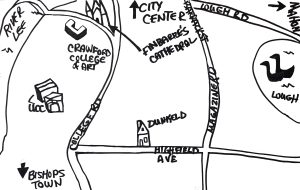

Mental Map

The purpose of this chapter is to increase our geographic awareness and to refine our geospatial thinking. Mental or cognitive maps are tools that we all use every day. As the name suggests, mental maps are maps of our environment stored in our brain. We rely on our mental maps to get from one place to another, to plan our daily activities, or to understand and situate events that we hear about from our friends, family, or the news. Mental maps also reflect the amount and extent of geographic knowledge and spatial awareness that we possess.

When mapping a place from memory, we learn from what is included and what is excluded, it tells us what’s important to the map maker.

Exercises

Exercise 1: Create a Mental Map (10 mins)

Using a blank sheet of paper, draw a mental map of a place you know well to help a newcomer get around. Do not look at an existing map or any other references. When you finish your map show it to someone else and ask for their feedback on your geospatial thinking and curation.